Anna Atkins: Pioneering Botanist and Creator of the First Photo Book

By Max Levin•July 2022•7 Minute Read

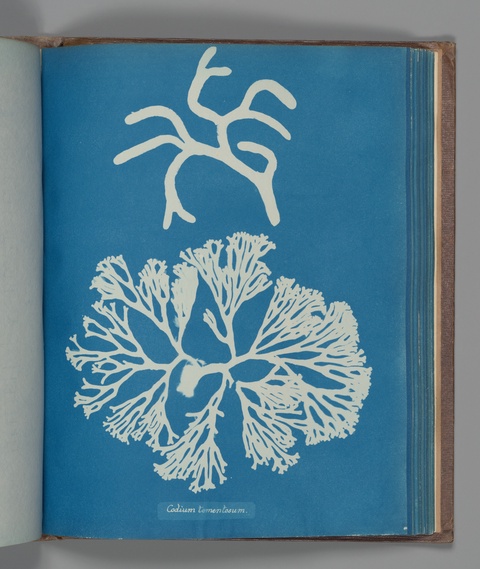

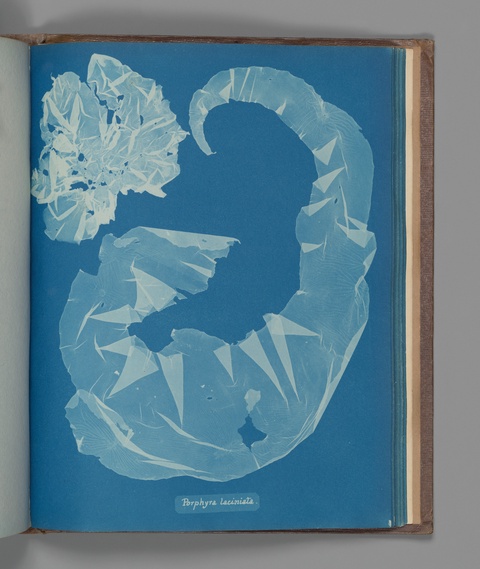

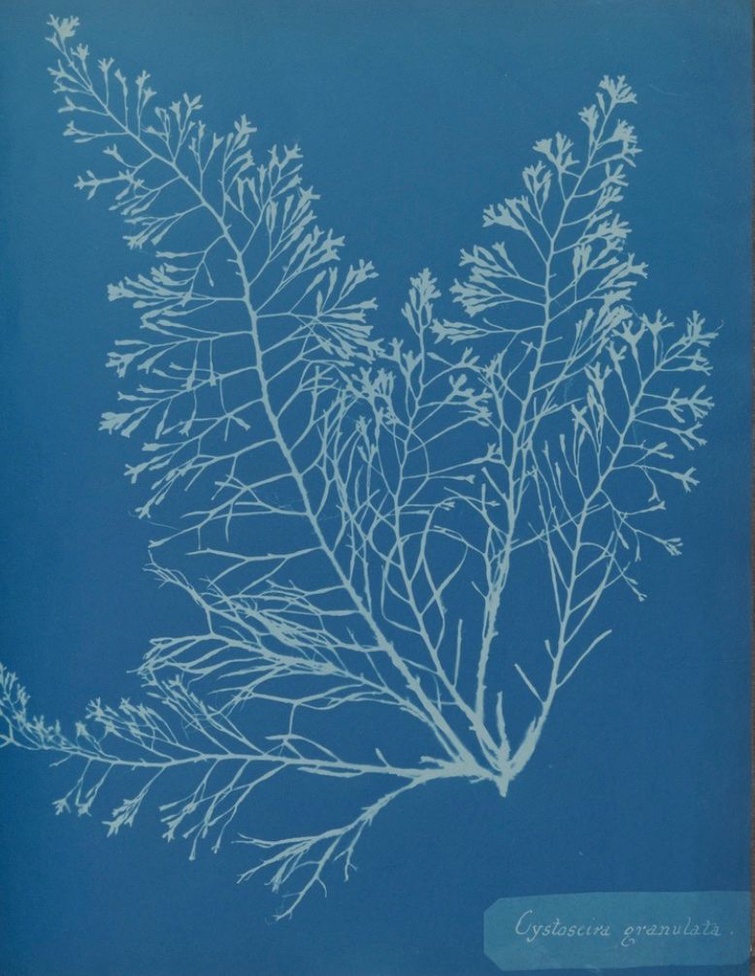

Anna Atkins, Cystoseira granulata, circa 1853. Metropolitan Museum of Art. A page from the first known photography book, a collection that used the early photographic technology of cyanotype to document British algae. Public Domain.

At the dawn of photography’s significant role in scientific study, Anna Atkins created the first photo book: cyanotypes of British algae.

Introduction

Anna Atkins (1799-1871) was an accomplished illustrator, pioneering botanist, and gifted image-maker. She produced some of the first photographic representations of ferns, algae, and other flora that were intended for close visual appreciation. By applying early camera and printing innovations to the systematic study of plants, Atkins left a significant legacy that has grown over the centuries. At the time, she approached her work as science, but it is now also seen as art. Her 1843 book Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions is considered the first photo book ever made.

Atkins used new photochemical processes and technical innovations to produce aesthetically engaging compositions. Her family connections to institutions of knowledge exposed her to relevant people and cutting-edge ideas. This allowed her special access to a nexus of several emerging bodies of thought—botany, taxonomy, and chemistry—which Atkins combined into something novel.

Early Life, Early Photography

John George Children and Hester Anne Children gave birth to their only daughter, Anna, in Kent, England in 1799.1 Hester passed away shortly afterwards. Daughter and father would maintain an especially close relationship throughout their lives.2 John Children was a respected chemist and zoologist, and the first president of the Royal Entomological Society.3 He was also secretary of the Royal Society, a longstanding fellowship of preeminent scientists of various disciplines, first formed in 1660. Due to her father’s personal tutelage and professional connections, Anna Atkins (née Children) was exposed to art and natural science from a young age.

By her twenties, Atkins was a skilled illustrator and demonstrated an affinity for carefully representing the subtleties of natural forms. She completed hundreds of drawings of shells for an 1822 encyclopedia.4 In the years to come, new innovations in imaging technologies would push Atkins beyond pencils and paper. William Henry Fox Talbot, the British inventor of photography, was a friend of Atkins’s.5 In 1834, unaware of what was happening in France, Fox Talbot devised a way to fix images on paper using light-sensitive chemicals. Talbot’s announcement of a negative-positive photography process that he called the calotype came just two weeks after Louis Daguerre’s announcement of the daguerreotype.6 Both of these inventions sparked a series of developments in imagemaking that informed the film photography processes we know today.

From Camera to Cyanotype

Atkins was also friendly with Sir John Herschel, an astronomer who was seeking a way to easily reproduce his notes.7 Herschel’s refinement of Talbot’s process became known as the cyanotype. He discovered that two chemical compounds—ammonium ferric citrate and potassium ferricyanide—could be applied to paper and then overlaid with an object in the sun to produce an image. The light energy transforms the exposed areas of the treated paper a bright Prussian blue, while the unexposed paper, shielded by the objects, creates a whitish image. Herschel sent Atkins his notes on the new cyanotype process in 1842.8 Shortly thereafter, Atkins embarked on a groundbreaking application of the new technique.

Fine Grained Representation

In the hundreds of years leading up to Atkins’s experiments, plant specimens and other natural forms were rendered primarily with drawing and painting. While drawings were satisfactory in their time, they were also often inaccurate due to misperceptions, biases, or the inability to render certain intricacies by hand. Even Leonardo da Vinci’s physiological and botanical studies, which preceded later scientific illustrations, were not immune from error. Da Vinci famously represented the uterus as a sphere, though it is now known to be pear-shaped.9

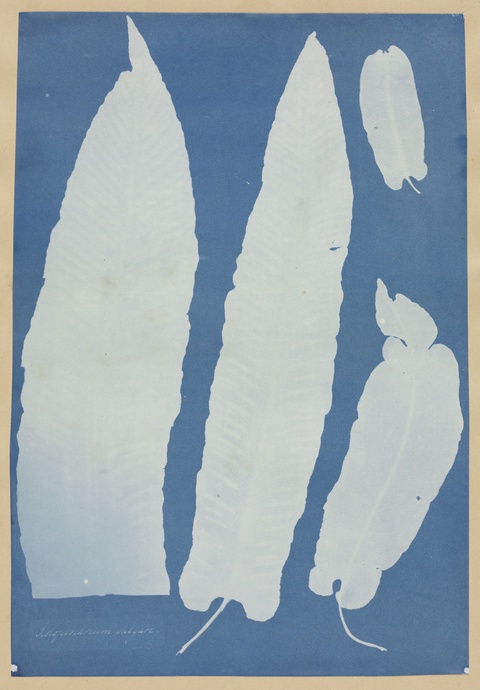

Herschel’s cyanotype process did away with errors of the hands or eyes. The sun could crisply expose even the haziest, most diaphanous forms. With this new method, Atkins realized that observation and composition could join with this new technology to produce a new kind of botanical representation. She went on to hand-develop hundreds of images of algae, ferns, seaweeds, and other specimens. Translucent areas filtered light to partially activate the chemicals, resulting in shades of blue. Atkins’s innovative images functioned as taxonomic resources for plant identification. They also happened to be beautiful.

The First Photo Book

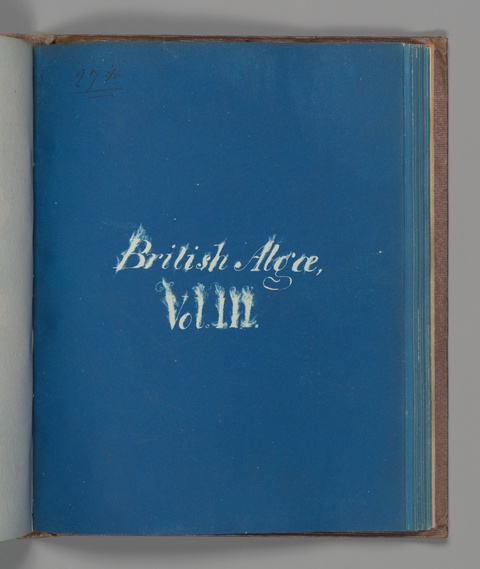

While fine drawings had previously illustrated many plant taxonomies, Atkins noticed a total lack of illustrations of algae.10 In 1843, she set out to produce photographic representations of algae and distribute the images in portable books. Atkins gathered more than 300 cyanotype impressions of algae species found in Britain and published them in a handmade, limited edition book called Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. For the first time, a book had been illustrated entirely by photography.11 Just eight months later, in June 1844, the first copies of Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature were published—the first commercially produced book of photographs.12

Atkins distributed copies of Photographs of British Algae to friends and experts in the field. They did not initially reach the audience or command the recognition that would come later, especially because the history of art did not at first include cyanotypes or even photography. Several of Atkins’s books found their way into the collections of the Rijksmuseum, the New York Public Library, and many other artistic and encyclopedic institutions across the globe. The 2018 exhibition Blue Prints: The Pioneering Photographs of Anna Atkins brought further attention to these groundbreaking images and the evolution of their reception.

Other Projects and Legacy

After the success of her first major photo book on algae, Atkins’s father passed away at his daughter’s home at age 74. She devoted herself to writing his biography. Afterward, she turned to producing cyanotypes of ferns. This later project resulted in the 1854 book Cyanotypes of British and Foreign Flowering Plants and Ferns.13 As a way of embracing the experimental nature of her projects, Atkins developed a cyanotype font for the title pages of her books based on her handwriting. In some cases, she composed the letters with bits of seaweed.

Alongside her books, Atkins collected herbarium specimens and supported varied printmaking projects, including cyanotypes of feathers.14 Six years before her death, Atkins donated her herbarium collection to the British Museum, further cementing her place as a conservationist and pioneer at the intersection of botany and art.15 The success of the cyanotype print, not only as an accurate image but as an archival material that will not fade, popularized the idea of a “blueprint.” More than any other early practitioner of the cyanotype, Atkins married taxonomic with photographic achievement and presaged massive industries of photography, art books, photo-based archives of natural materials, and more.

Citations

"Anna Atkins." Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Anna-Atkins. Accessed May 30, 2022.

Lotzof, Kerry. “Anna Atkins and the First Book of Photographs.” Natural History Museum, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/anna-atkins-cyanotypes-the-first-book-of-photographs.html. Accessed May 30, 2022.

Moorhead, Joanna. “Blooming Marvellous: The World's First Female Photographer – and Her Botanical Beauties.” The Guardian, 23 June 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/jun/23/blooming-marvellous-the-worlds-first-female-photographer-and-her-botanical-beauties. Accessed May 30, 2022.

“Anna Atkins and the First Book of Photographs.”

“William Henry Fox Talbot.” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections/william-henry-fox-talbot. Accessed May 30, 2022.

Whitmire, Vi. “William Henry Fox Talbot.” International Photography Hall of Fame, 19 August 2016, https://iphf.org/inductees/william-henry-fox-talbot/. Accessed May 30, 2022.

"Sir John Herschel, 1st Baronet." Encyclopædia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Herschel. Accessed May 30, 2022.

“Blooming Marvellous.”

Delany, Samuel R. “The Rhetoric of Sex / The Discourse of Desire.” Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts & The Politics of the Paraliterary, Wesleyan University Press, Hanover, 1999.

“Blooming Marvellous.”

Annemarie Iker. “Anna Atkins: Moma.” The Museum of Modern Art, 2020, https://www.moma.org/artists/231. Accessed May 30, 2022.

“William Henry Fox Talbot.” The Getty Museum, https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103KJK. Accessed May 30, 2022.

Schaaf, Larry J. “The Cyanotypes of Pioneering Photographer Anna Atkins.” National Gallery of Canada, 26 Nov. 2020, https://www.gallery.ca/magazine/your-collection/the-cyanotypes-of-pioneering-photographer-anna-atkins. Accessed May 30, 2022.

“The Cyanotypes of Pioneering Photographer Anna Atkins.”

“Anna Atkins and the First Book of Photographs.”