Bathing Women: Desire, Wonder, and Water in Versions of a Persian Tale

By Shweta Sachdeva Jha•August 2024•16 Minute Read

Iran, probably Tehran, Tile depicting Khusrau Happening upon Shirin Bathing, late 19th century. Art Institute of Chicago, public domain.

Scenes with women bathing outdoors, presented as erotic sites of romance or devotional love, reveal socio-historical mores on sexualities, piety, and the symbolism of water. Renditions of Shirin bathing from a classic Persian romance connect female bodies with water bodies.

Interconnecting Bodies: Bathing Women in Waterscapes

Visual representations of bathing women embed historically and culturally specific ideas of female sexualities, nudity, and desire. Scenes of women bathing in natural bodies of water such as ponds, streams, waterfalls, and rivers have been rendered in paint, molded in sculpture, and woven into silks. Visually conjoined, female bodies and natural waters impress as autonomous, life-giving and immensely powerful. Analysis of different artistic adaptations of this single scene can unhinge misconceptions of “Islamic” art and reveal the nuances of historical confluences from Iran, Central Asia, to the South Asian subcontinent.

In a world threatened by fundamentalist thought that dangerously asserts religious differences and ignores climate change and its accompanying disastrous droughts and floods, reading this scene can be empowering in three ways. First, this bathing scene shows us the symbolic significance of water and the aesthetically expressed interlinks between femininity, desire, power, and spiritual practices in Perso-Islamic cultures. Second, these representations challenge simplistic assumptions of Iranian womanhood and force us to rethink concepts of desire, agency, and voyeurism. Third, these objects reveal the important cultural role played by women amid natural waterscapes. Fecund, sensual, and life-giving, the female bodies in these scenes can bring “feminist insights into intercorporeality.”1 As contemporary spectators, interrogating the historical denotations of each art object can reveal shared histories of female bodies and bodies of water.

Nudity, Desire, and Bathing Scenes

In pre-modern art, bathing scenes with women’s bodies in different stages of undress, nudity, or at the toilette are common. In Greco-Roman, Renaissance, and Perso-Islamic cultures, the female nude body is distinct from a naked body in its idealistic representation of beauty, perfection, and philosophical symbolism.2 When shown alone, the bathing woman is usually a goddess, a famous literary character, or an archetype, while women bathing together represent nymphs, royal ladies, or characters from mythological tales or legends.

In this 17th century folio, a group of eight women undress to swim and bathe in a marble pool on a moonlit night. While most are in the pool, some women are busy in conversation or resting beside the holy peepul tree. In this laid back scene painted within a framing border, the women look comfortable in each other’s company. Outside the border, seven fully dressed women participate in the ritual adornment that follows the bath: some play with strings of pearls, probably discuss jewelry as they observe the pieces, and others carry perfumes and containers. Back at the pool, the women are unaware of the presence of a turbaned, male onlooker nearby. Was he an attendant, a stranger, a voyeur? The answer lies in his gesture of biting a finger. This is often used for Khusrau, a royal prince in Persia who is commonly shown biting his finger when astonished by the beauty of bathing women, in particular that of the woman who becomes his wife.

A Tale of Desire and a Bathing Woman: Shirin and Khusrau

One of the most celebrated and widely illustrated scenes of lovers first meeting features a bathing woman. This ubiquitous scene of Khusrau coming upon Shirin bathing in a stream or a river is from a medieval Persian romance, popular across the Persianate courts in Iran, Central Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. It was widely reproduced in illustrated and illuminated manuscripts, molded on tiles, and even woven into silk and velvet fabrics.

The Various Narratives of Khusrau and Shirin

The central romance is set in the context of the historical conquests of Khusrau II (r. 590–628), the last Sasanian King of pre-Islamic Iran, and narrates his love for the Armenian Christian Princess, Shirin, who later becomes his wife and the Queen of Persia. The most famous retelling is a long narrative Persian poem by Nizami called Khusrau and Shirin. The poem itself is part of a Khamsa, a quintet of five stories.3 From the 16th century onwards, the khamsa of Nizami and Amir Khusrau were illustrated in both Iran and India.4 By the 18th century, India had more speakers of Persian than Iran.5

Nizami’s long poem is celebrated for its depiction of the lovers, Khusrau and Shirin, their devotion and passion, and as a text that gives us “psychological insights meant to illustrate philosophical theories of human love.”6 In Nizami’s version, Khusrau sees his grandfather in a dream, who tells him of the beautiful Shirin, his love and his destiny.7 When Khusrau hears about the beauty of Shirin, he asks his friend Shapur to bring her to him. Shapur, a painter, draws portraits of the handsome prince and strategically places them in Shirin’s way to ensure that she falls in love with Khusrau.

Shirin holds the portrait of Khusrau while being watched by Shapur, mid-16th century. Saint Louis Art Museum, public domain.

In this painting from a Khamsa manuscript, the artist is hiding behind the tree and watches Shirin admire the king’s portrait handed over by a female attendant. Soon Shirin is in love and desires to leave Armenia to go to Persia in search of her beloved. On the pretext of going on a hunt, she leaves with her stallion, Shabdiz.

After traveling for 14 days and 14 nights, she comes upon “an emerald field in which there gleamed a gentle pool.”8 She looks around to check if she is alone and then tethers her horse and prepares to take a bath. Loosening her braids, she washes herself in the cool, refreshing water.9 Meanwhile, Khusrau has had to flee Persia due to complications at the court. The king comes upon Shirin while she is bathing and “his heart caught fire and burned; he trembled with desire in every limb.”10 Shirin looks up, startled, covers her naked body with her hair, and emerges from the pool. Neither of the lovers recognize each other. Shirin gets dressed and rushes off.

In Firdausi’s Shahnama, or The Book of Kings, Shirin is a minor character, a scheming courtesan who ensnares Khusrau by staging this bathing encounter.11 However, Nizami’s text has been more famous, and here Shirin appears as a modest princess who will become the queen.

Visual Depictions of the Lovers’ Meeting from the 14th to 19th century

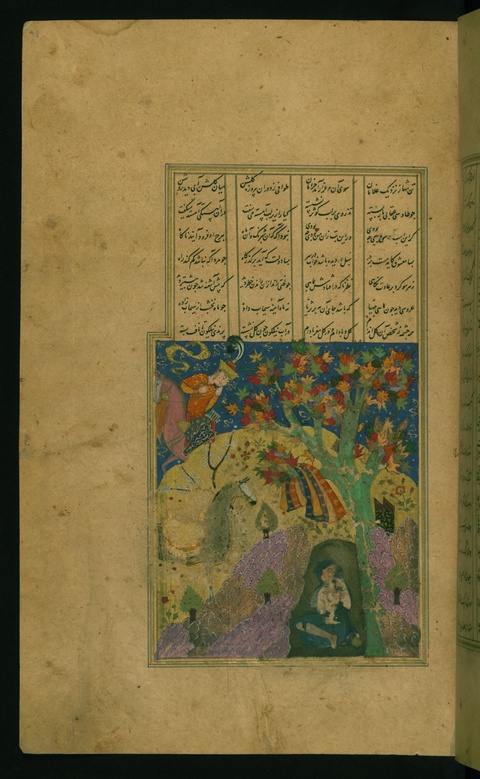

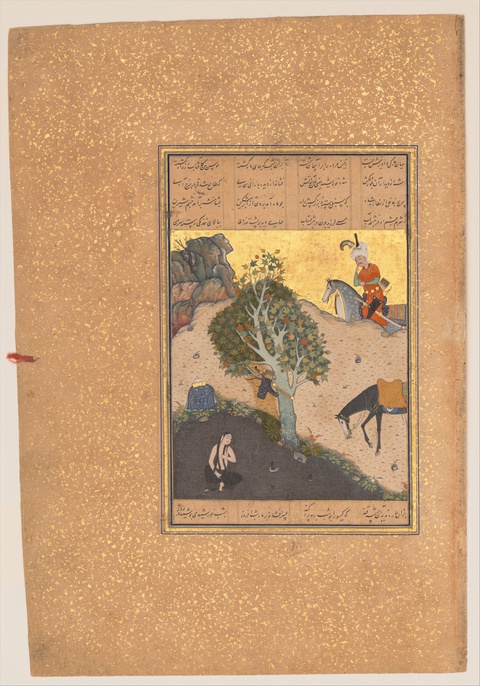

Since the 14th century, Persian artists have played with the setting and composition of the lovers’ meeting. In this 15th-century miniature painting from a folio in Iran, the artist sets up a verdant backdrop, showing Shirin’s royal robes and crown hung on the tree while the black stallion stands like a guardian behind her.12 Although here, as in the poem, the natural waterbody is a pool, others depict her bathing in a river, a stream, or a spring. Across various khamsa manuscripts written in Persian calligraphy, each rendition of the bathing scene is aesthetically distinct in its depiction of waters, the clouds, the sky, the foliage, colors, costumes, headgear, and even physical features of the lovers as well as the interplay of their gazes.

Framing Devices and Interplay of Gaze

This 16th-century khamsa boldly shows the lovers looking directly at each other, a moment of rapture and desire. While Shirin bathes in a spring, her clothes once again hang provocatively on the tree branches between them.

In this folio from 1517–18, Shirin bathes in a flowing stream while the sky is bright gold. Shabdiz stands guard but a part of him extends past the left side of the painted frame. In Persian miniature paintings, characters break out of the frame to signify a momentous event like this—the lovers’ first meeting. In some paintings, such as the next one, artists used silver for the pool (which has tarnished and turned black with time) and gold for the shades of the sky. Like in many depictions of this meeting, the tree bearing her clothes, Shabdiz, and the stream act as visual barriers symbolic of natural desire, power, and passion, and yet meant to separate the two lovers.

Read in close proximity, these paintings all not only depict Khusrau gazing at Shirin, but create a mirror in the reader’s prolonged gaze at her naked body. Because this could evoke feelings of lust, in some visual renditions Shirin’s naked body is effaced or smudged “to tone down the sensuality of the image.”13 This has little to do with the oft-repeated if inaccurate notion of Islam having a universal aversion towards all figurative imagery, but rather concerns the “anxiety towards the power of erotic images.”14

For some readers, Khusrau’s encounter with Shirin represents mundane or earthly love, while to others, his quest is a symbolic search for divine love.15 Khusrau is rendered speechless and bites his finger in this wondrous moment of silence, marveling at Shirin’s divine beauty. Her beauty will eventually lead him on the path of Sufism. Depending on the patron and the spectator, Khusrau and the young male figure in the Shah Jahan Album might represent a voyeur, an intoxicated lover, or a seeker of divine love.

Of Sufism and Silks

Religious-minded patrons were also interested in the scene of the first encounter. This silk and velvet fragment gives us part of the famous bathing scene, the giveaway being that Shirin’s clothes and crown are hung on a branch, even though the stream is not visible. Khamsa silks were woven by craftsmen and were luxury commodities in early modern Safavid Iran (1501–1722).16 These silks were meant for use as luxury dress and held great iconological significance among weavers, many of whom were followers of Sufism, as well as patrons who bought these items.17

The owner of this dress could signal both his high status through the figure of Khusrau as well as his association with the mystic Sufi quest for divine love, both romantic longing and transcendental, all-encompassing union.

From Intimacy to Courtly Display

In the manuscripts, the sight of Shirin’s bathing body becomes a part of an intimate moment of reading. As years pass, the scene gets incorporated in fashionable woven fabrics. By the mid-18th century, illustrations of this scene were even made on large wall displays in palaces and courts.

This 18th-century oil painting from the Zand Iranian court shows a bathing Shirin with rounded breasts and visible bodily curves unlike the more demure miniature paintings. Although her female attendant is ready to drape a sheet over her, she is twisting her head to look back at Khusrau bestride his horse. He returns the gaze.

Khusraw Discovers Shirin Bathing, From Pictorial Cycle of Eight Poetic Subjects, mid-18th century. Brooklyn Museum, CCO. The bathing Shirin notices Khusrau watching her, while an attendant tries to drape her and Shapur looks on.

In this painting, ornaments on Shirin’s hair, the pearl necklace hanging around her neck, and the detailed contours of her body and prominent breasts assert the courtly wealth of the patron and draw the spectator’s gaze towards her body. Shaped to fit a wall, such large-scale arched oil paintings on canvas featuring princes and historical scenes adorned palaces and reaffirmed courtly wealth and power.18

Even in the late nineteenth century, Shirin’s naked body continued to find a place in public architecture, for instance in the form of tiles. In this glazed, fritware tile from the Qajar period, Shirin is seated on what appears to be a casket while holding a comb.19 Elements borrowed from royal hunting scenes, such as rabbits and the lion on the bottom right, now turn the bathing Shirin into a courtly possession akin to the decor depicted in the scene, taking away her powers of agency and desire. Some tiles were sold individually to Europeans while others were part of multi-part friezes that decorated interior and exterior walls of many secular buildings.20 Khusrau is not alone as he gazes upon Shirin anymore. A large number of visitors could simultaneously look upon this scene on the wall.

In the early Qajar period (1785–1925), notions of beauty were largely undifferentiated by gender and art featured beautiful men and women with very similar bodily and feminine features. If we look closely at Shirin and Khusrau, they appear almost alike. Female and male beauty could be described using the same adjectives in literary texts and depictions of royal beauty shared a visual iconography at this time.21 Therefore the scene with bathing Shirin could evoke “multiple circulations of desire” among spectators.22 With increasingly overlapping gendered notions of beauty, the association of womanhood with water reduces, streams and rivers recede in the artistic representations.

Intercorporeality: Female Bodies and Bodies of Water

Bathing scenes in the outdoors can be erotic as well as symbolic of divine beauty, depicting women and waters as sacred and life-giving. Contesting gender binaries and hierarchies between human and nonhuman, Astrida Neimanis calls us to think of rivers, streams, and ponds as the primordial soup from which all genders and the flora and fauna we know today have emerged.23

Female Bodies of Pre-Modern Waters

Women and water have a long intertwined presence as river goddesses, nymphs, lovers, devotees, and literary representations in Perso-Islamic mythologies. We can locate Shirin within this lineage of women with wisdom, fertility, and agency.

In this silver gilt dish from the Sasanian Empire in Iran, Goddess Anahita is shown dancing, as berries and vines symbolic of fertility frame her nude body. Anahita was an old Persian name for the goddess of waters, fertility, healing, and wisdom in pre-Islamic Iran.24

From Anahita to Shirin, waters and female bodies express sensuality, fertility, desire, and furnish soulful symbols of divine wonder. The miniature paintings of Shirin bathing are rich in their use of iconography and the symbolism of waters associated with bountiful Islamic gardens. Water is the source of all life on Earth but, in the Persian garden, “it represents the eternally-flowing waters of Paradise. Importantly, water is symbolic of the soul—sometimes restful in a still pool, sometimes energetic when it is flowing fast.”25 Subsequently, the intercorporeality of female bodies with water bodies begins to recede as we move towards modernity. The threat of the anthropocene looms large, with impending water shortages and threatened coastlines. Forgotten histories of female bodies and waters from pre-Islamic times show us how gender, sexualities, and waters connect.

Shweta Sachdeva Jha is a 2024 Curationist Fellow. She is an Associate Professor of English at Miranda House, University of Delhi. Her research lies within interstices of histories, archives and literature anchored by a feminist core. She did her doctoral studies as a Felix Scholar at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Her research publications range from studies of contemporary children’s picture books in India, history of tawa’if (courtesans and Nautch Girls) in colonial India to digital archives on college women and twentieth century genre fiction in Urdu by Muslim women. Recently awards and small grants have helped her begin a new journey into digital history, archives and writing on the visual arts.

Citations

For the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, intercorporeality meant bodies interconnected with other bodies, and the interrelations between objects and subjectivity. For more on him, see www.plato.stanford.edu/entries/merleau-ponty/. The philosopher and artist Astrida Neimanis borrows this concept and proposes hydrofeminism to bridge feminist thought, posthumanism, and environmental concerns about water. See Neimanis, Astrida. Bodies of Water: Posthumanist Feminist Phenomenology, 2017.

To understand the distinction between nakedness and nudity, see Sorabella, Jean. “The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 2008, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/nuan/hd_nuan.htm. Accessed 12 July 2024.

The Khamsa was a quintet of five stories also called the Panj Ganj or the Five Tales. See https://www.worldhistory.org/Khamsa_of_Nizami/. Each tale is told in a long poem called a masnavi.

Famous Persian poets such as Firdausi (940–1019/1025 CE), Nizami (c.1141–1209) of Ganja, and the Sufi mystic Amir Khusrau (1253–1325) of Delhi, wrote about the two lovers.

Bend, Barbara. “From Persia and Beyond: a discussion of the illustrations to a Khamsa of Amir Khusrau Dihlavi in the State Library of Victoria.” La Trobe Journal, June 2013, no. 91, pp. 97–107, https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/stories/la-trobe-journal/la-trobe-journal-no-91-june-2013. Accessed 12 July 2024.

Van Ruymbeke, C. “Persian Medieval Rewriters between Auctoritas and Authorship: The Story of Khusrau and Shirin As a Case Study.” Brill, 2017, p. 13, https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.11586. Accessed 11 July 2024.

The quotations from the story are taken from this English translation of the masnavi: Chelkowski, Peter J et al. “Khosrow and Shirin.” Mirror of the Invisible World: Tales from the Khamseh of Nizami, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975, pp. 21-48, https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/Mirror_of_the_Invisible_World/aYSzcOVMvRAC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover Accessed 11 July 2024.

Chelkowski, p. 22.

Chelkowski.

Chelkowski, p. 27. Poets like Nizami dedicated long passages describing her beautiful body from head to toe. This type of poetic description was common to Sanskrit (nayika bhed), Persian (sarapa), and Italian and English (blazon) poetry. Haq, Syed Nomanul. “Whither portraiture? The poetic resilience of sarapa.” Dawn, 8 September 2013, https://www.dawn.com/news/1041197. Accessed 16 July 2024.

Van Ruymbeke, p. 9.

These folios made up the khamsa in which a scribe copied Nizami’s text using nasta'liq calligraphy and artists made illustrations. Each khamsa was a collectible, often bound in leather and sometimes gold.

Agarwala, Seher. “Her Black Hair Seduced Hearts and Souls, Her Moon-face Astonished Intellects: Desire in Khursrau o Shirin.” The Long Arc of South Asian Art: Essays in Honour of Vidya Dehejia, ed. Annapurna Garimella. Women Unlimited, Marg Publications, 2022, pp. 256-276.

Agarwala, p. 262.

Mundane or earthly love was love between two human beings, longing and eros, which was called ishq-e-majazi (earthly love), while divine love was referred to as ‘ishq haqiqi. For Sufi mystics, the ultimate divine love was to lose the self in God and through this spiritual knowledge seek union with God or Allah.

Khamsa silks are part of a larger genre of figural textiles that were in demand as luxury objects throughout Eurasia.

Munroe, Hedayat N. “Introduction: Material Culture and Mysticism in the Persianate World.” Sufi Lovers, Safavid Silks and Early Modern Identity. Amsterdam University Press, 2023, pp. 17–24.

Zand artists introduced decorative elements such as ornaments and figurative style and were also influenced by European art during that time. For more on portraiture by Zand artists, see Sims-Williams, Ursula. “Some portraits of the Zand rulers of Iran (1751-1794).” The British Library, https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2014/06/some-portraits-of-the-zand-rulers-of-iran-1751-1794.html. Accessed 12 July 2024. On different artistic styles across historical contexts in Iran, see Kianush, K. “The Zand and Qajar Periods.” Art Arena, http://www.artarena.force9.co.uk/zandqajar.htm. Accessed 12 July 2024.

For more on how artists added details like combs to draw attention to Shirin’s tresses, see Agarwala, p. 269.

The decorative framing design and the shades of turquoise, cobalt blue, pink, and brown were influenced by Chinese pottery, which also made these tiles coveted objects. Shirin’s seat carries an inscription, “The Servant of the Court of Aga Jan wrote it.” Aga Mohammad Shah was the founder of the Qajar dynasty of Iran and ruled from 1789 to 1797. The inscription clearly emphasizes the tile as a courtly object made in the reign of the Qajar ruler.

Najmabadi, Afsanah. Women with Moustaches and Men Without Beards: Gender and Sexual Anxieties of Iranian Modernity, University of California Press, 2005, pp. 11–13, 22–23.

Najmabadi, p. 48.

Neimanis, p. 4.

Scholars have traced links between Anahita and Goddess Saraswati (“She who possesses waters”) of knowledge, arts, and wisdom worshiped in Vedic India. “Anahid,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, www.iranicaonline.org/articles/anahid. Accessed 12 July 2024.

Clarke, Emma. “The Islamic Paradise Gardens and the Garden Within”. www.agakhancentre.org.uk/past-exhibitions/making-paradise/the-islamic-paradise-gardens-and-the-garden-within/ Accessed 12 July 2024.

Shweta Sachdeva Jha is a 2024 Curationist Fellow. She is an Associate Professor of English at Miranda House, University of Delhi. Her research lies within interstices of histories, archives and literature anchored by a feminist core. She did her doctoral studies as a Felix Scholar at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Her research publications range from studies of contemporary children’s picture books in India, history of tawa’if (courtesans and Nautch Girls) in colonial India to digital archives on college women and twentieth century genre fiction in Urdu by Muslim women. Recently awards and small grants have helped her begin a new journey into digital history, archives and writing on the visual arts.