Swords that Tell Stories: Plunder and Trade from India to Europe

By Reina Gattuso•June 2022•9 Minute Read

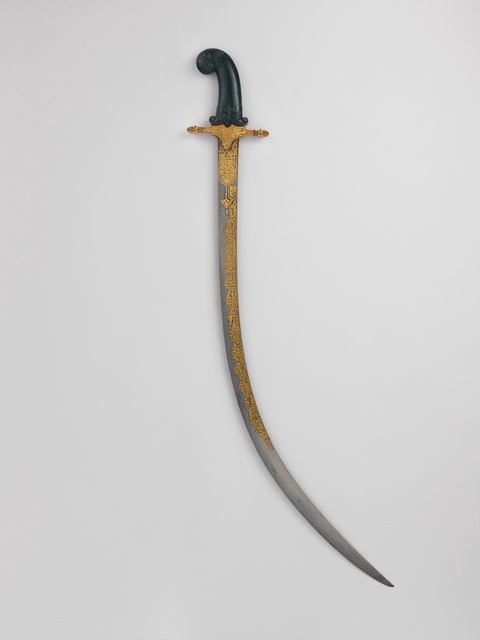

Unknown, Saber with Scabbard, 18th and 19th centuries. Metropolitan Museum of Art. An Ottoman sword composed of a Persian blade, an Indian jade grip, and an Ottoman guard and scabbard.

The story of one sword can span thousands of miles and hundreds of years. From the Mughals to the Mamluks, medieval and early modern empires traded and plundered these valuable weapons. Swords traveled between Asian and European empires, picking up valuable decorations and powerful inscriptions along the way.

Introduction

From the 1400s to the 1800s, soldiers often took their enemies’ swords as trophies. Conquering kings sacked their neighbors’ royal armories.1 Plunder and trade were both strategies to raise arms. And so, like their owners, historical swords traveled.

Sword making required great skill and expense. Swordsmiths refitted blades and hilts, embellishing them to create new swords. Particularly in Islamicate cultures, monarchs passed down ceremonial swords, often encrusted with precious gems and inscribed with prayers and protective magic.2

Many swords of this period have hilts crafted in one or even two empires and blades forged in another. By examining these modifications, we can trace a sword’s unique story against a backdrop of geopolitical and technical change. For example, a European sword from the 1400s, kept in an armory at Alexandria, marks the period of Arab ascendancy in the Mediterranean. South Indian swords with European blades from the 1600s show the growing British, French, and Portuguese influence.

Crafted for battle in the finest forgeries of Eurasia, these swords have ended up displayed as art objects in the United States.

Trade and Plunder from Anatolia to South Asia

The medieval and early modern periods were a time of great Asian empires. The Safavids in central Asia, the Ottomans in the Mediterranean, and the Mughals in South Asia all ruled over expansive, cosmopolitan territories.

These empires’ royal treasuries and armories were filled with plunder from war, including precious swords. Victorious rulers often commissioned their craftspeople to embellish and refit these swords, adding decorative and magical elements. Art historians can use these elements to trace the provenance of an individual sword.

For example, the gem-studded jade hilt of the sword pictured below is characteristic of a kind of Mughal dagger called a chilanum. This indicates that the hilt might have come from the Deccan region in South Asia. The blade has a cutout strung with precious beads, a popular style across Central and South Asia starting from the 16th century.3

Art historians are not sure whether there was one center of craftsmanship that produced most of these blades or whether swordsmiths across Asia imitated the style. They can only guess that the blade came from either Anatolia or South Asia—a testament to how far swords ranged.4

Similarly, the elements of this saber ended up in an Ottoman treasury after an elaborate journey through Asia. Mughals made the 18th century jade grip. The curved steel blade is probably Persian in origin. The Ottomans likely traded or captured swords with these elements. Ottoman swordsmiths crafted the gold guard and united the parts. By the early 1900s, the sword was in an Istanbul treasury.

The writing on sword blades also helps us trace their journeys. In Muslim dynasties, sword makers often inscribed sword blades with Quranic verses and symbols like the Seal of Solomon to protect their users.5 This sword contains both.

Owners often inscribed their names, or the names of powerful ancestors, on their swords. The writing on this sword invokes the lineage of the great Ottoman Sultan Suleiman Khan. This doesn’t necessarily mean the sword’s owner was descended from the Sultan. They may simply have wanted to invoke the royal authority of a powerful historical figure.

Ottoman Sultanship and Diplomacy

Lavishly decorated swords were an important part of Ottoman court practices. Ottoman sultans received swords upon their accession to the throne, and they gifted swords to other rulers as part of diplomacy. Royal sword makers often constructed swords with elements from other empires already kept in the royal treasury, demonstrating the Ottoman Empire’s reach.

This scimitar was likely a diplomatic gift. Ottoman artists made the hilt and scabbard. They showed off Ottoman wealth by bejeweling the scabbard so lavishly it may as well be a small, mobile treasury. The Ottomans used this kind of highly decorated weapon for parades and other state occasions. At some point after the scabbard’s creation, an owner fitted it with a Persian blade.

Ottoman officials often gave these ceremonial weapons as diplomatic gifts, and many ended up in European treasuries.6 Indeed, Spanish historians documented this sword in the Madrid Royal Armory in 1898.7

The saber below played an important part in Ottoman royal succession. Royal sword makers assembled it, using items likely already in the treasury, for sultan Murad V’s 1876 inauguration. The swordsmith chose a Persian blade from the 1600s. The jade grip is from India and was likely made in the 1700s.

Ottoman sword makers added their own scabbard and lavished it with gold and precious gems. Inside a secret compartment on the sword, artists placed a gold coin inscribed with the name of Süleyman the Magnificent.8

If Murad hoped the coin would bring him Süleyman's good fortune, however, he was mistaken: Murad was deposed within 93 days of his inauguration.

Indian Artisans and Firangi Blades

From the 1600s–1800s, the Mughals were the most powerful empire in India and had the largest economy in the world.9 However, Indian swords from the period reflect a growing European influence.

The Indian subcontinent was and remains religiously diverse. Swords may have changed hands between owners of different faiths. Religious decorations like Quranic calligraphy or representations of Hindu gods help us understand the cultural context of the sword’s owner and reflect their prayers for safety in battle.

Many Indian swords of this period had local hilts with firangi, or European-style blades.10 Local artisans would then adapt the blades. The owner of the firangi blade above had it inscribed with Quranic verses in the form of a talismanic scroll, a kind of protective magic.11 This sword has a locally made hilt.12

Most South Indian kingdoms of the time officially patronized Hinduism. This dagger, called a katar, reflects Hindu influences as well as extensive contacts with the Portuguese and Dutch.

The katar has a European straight blade and a South Indian-style grip. The user would have put their fingers through the opening to grip the dagger. The swordsmith decorated the sides of this grip with images of the ten avatars of the Hindu god Vishnu, perhaps to glorify the god and bring good luck to the owner.13

Swords at the Border of Europe and Africa

During this period, the boundaries between Muslim and Christian dynasties in Europe and North Africa were constantly shifting. The Muslim Nasrids ruled southern Iberia for most of the 1400s. As the Kingdom of Granada was declining, Ottoman power rose. By the late 1600s, the Ottomans controlled territory from Algiers to Budapest to the Caspian Sea. This expansion meant war—and thus swords used and captured in battle.

The sword below has traveled through four continents. The cross marking Its blade indicates that the original owner was probably Christian. That, coupled with the sword’s style, shows that it was likely made in Europe. Meanwhile, an Arabic inscription on the blade says that an owner donated the sword to the armory in the Mamluk city of Alexandria in 1419.14

From this, art historians surmise that an artisan made the sword in Europe before 1419. A North African soldier may have taken the sword as plunder during a Crusades-era clash with a European army in the Aegean or Levant. Or, the king of Cyprus may have sent the sword to a Mamluk sultan as tribute.15

When the sword was donated to the Alexandria arsenal, it entered a large collection of other European arms. The Ottomans captured Alexandria in 1517. At some point, the Ottomans brought this sword back to Istanbul. They kept it in the Ottoman arsenal until 1922, when a New York buyer purchased it and brought it to the United States. That owner bequeathed it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art upon his death in 1928.16

African and Asian swords influenced European weapon making. The sword below is called a kilij, or “pistol grip.” Kilijs originated among ethnically Turkic people, and the Mamluks and Ottomans both used them. When Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798, his soldiers brought kilijs back. European and North American militaries adopted the shape.

This particular kilij sports a bit of trickery. The scabbard and hilt were made in either Anatolia or North Africa in the 19th century. Its steel blade, meanwhile, bears the signature of Haji Sunqur, a famous 16th century Istanbul-based swordsmith. But this is impossible, since art historians surmise that the blade was made in Iran in the late 18th or early 19th century.17 Perhaps the person who added the signature was looking to make themselves seem more important—or inflate their sword’s value.

Conquest and Exchange

The swords featured above are all fearsome instruments. Their owners likely used them to kill other human beings. Soldiers stole them and sultans used them to symbolize ruthless might. They are the ultimate embodiment of the saying, “To the victor goes the spoils.”

Yet these objects also demonstrate a strange irony. Swordsmiths across empires mixed and refitted different elements of the swords, until the objects came to embody multiple cultures—including states that might have been at war with each other. In this way, the same blades used to sever human ties also testify to them.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.

Citations

“Saber.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/24319. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Saber with Scabbard.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/22871. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Dagger with Sheath.”The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/24298. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Dagger with Sheath.”

“Saber”

Catálogo Histórico-Descriptivo de la Real Armeria de Madrid. Maxtor Editorial, 2008, pp. 372. Google Books, https://www.google.com/books/edition/REAL_ARMERIA_DE_MADRID_CATALOGO_HISTORIC/yrPbYQxOkrgC?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Saber with Scabbard.”

“Economic History of India.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_history_of_India. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“A Gold-Damascened Steel-Hilted Sword (Firangi).” April 2013. Christie’s, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5671427. Accessed 30 March 2022.

Al-Saleh, Yasmine. “Amulets and Talismans from the Islamic World.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tali/hd_tali.htm. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Sword from the Arsenal of Alexandria.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/23189. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Dagger (Katar).” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/24305. Accessed 30 March 2022.

“Sword from the Arsenal of Alexandria.”

“Sword from the Arsenal of Alexandria.”

“Sword from the Arsenal of Alexandria.”

“Sword from the Arsenal of Alexandria.”

“Saber (Kilij) with Scabbard.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/31300. Accessed 30 March 2022.

Reina Gattuso is a content writer on the Curationist team, and an independent journalist covering gender and sexuality, arts and culture, and food. Her journalism connects analysis of structural inequality to everyday stories of community, creativity, and care. Her work has appeared at Atlas Obscura, The Washington Post, Teen Vogue, The Lily, POPSUGAR, and more. Reina has an MA in Arts and Aesthetics (cinema, performance, and visual studies) from Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, India, where her research focused on sexuality in Hindi film. She writes and teaches writing to high school students in New York City.